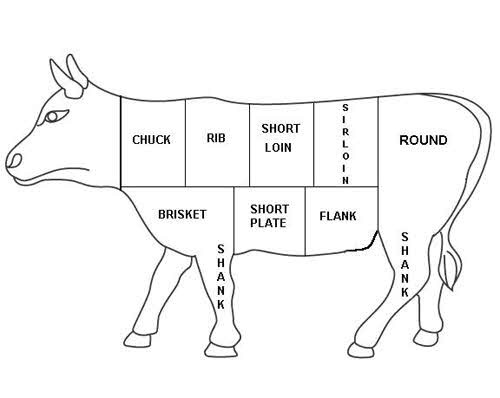

The Belly of the BeastFOOD FOR THOUGHT - July 08, 2009 - Mark R. Vogel - Epicure1@optonline.net Mark’s Article Archive When cooking beef the first, and often most confusing thing to master, is learning all the varied cuts. Beef is muscle tissue and like any living creature, different muscles possess different physiological qualities. The crux of the matter for the chef is the inherent tenderness/toughness of a particular cut and therefore, the best approach for cooking it. The most basic axiom, of which there are of course exceptions, is tender cuts of meat require dry-heat cooking methods and tougher cuts demand wet-heat cooking methods. In general, the tender cuts hail from the rib, short loin and sirloin while the tougher cuts are found in the chuck, brisket, round and shank, (see the diagram below). You’ll note that the tougher cuts involve muscles that see more action, i.e., muscles that allow ambulation or that bear the burden of the beast’s weight. The tender cuts are muscles that have less direct stress placed upon them. Just like human beings, the more a muscle is exercised the firmer it will be.  |

Dry-heat cooking methods, as the name implies, do not involve moisture, or more technically, an exchange of flavor with a liquid medium. They encompass grilling, broiling, sautéing, roasting, pan-frying and deep-frying, (oil is a lipid, not a water based fluid). The wet-heat cooking methods are braising, stewing, poaching, simmering, steaming and boiling. When naturally tender meat is exposed to wet-heat cooking or when naturally tougher meat is exposed to dry-heat cooking, the results are the same: shoe leather and inferior flavor. Tougher cuts of meat have higher amounts of connective tissue. Slowly cooking them in fluid, such as when making a pot roast or beef stew, gently breaks down these fibers and denatures the proteins within them to produce a supple result. Naturally tender cuts of meat have less connective tissue. Wet-heat cooking would merely drain them of their succulence. Thus, they require high, dry heat to quickly sear them without robbing them of their intrinsic juiciness. This is why you grill, broil or sauté a rib steak, or roast it if it is a larger cut.

As stated, there are always exceptions. Welcome to the beguiling cuts from the short plate and the flank, the belly of the beast. These cuts are, in a manner of speaking, somewhere between the extremes of the tender/tough dichotomy I outlined above. On one hand, they receive regular use as they play a role in the animal’s breathing. However, the gentle process of respiration is not as demanding on those muscles as the process of walking is on the legs. So these cuts will be noticeably tougher than a fillet mignon, but not as forbidding as a brisket. Moreover, they are not, biochemically or anatomically speaking, tough enough to be amenable to wet-heat cooking methods. Thus, you will need a dry-heat procedure. What these cuts do have however, is great flavor. Like everything in life there is a trade-off. Generally speaking, tender cuts are not as flavorful as the tougher cuts. Exercise, while rendering a muscle stouter, also imbibes it with nutrients that augment its flavor. Therefore, the cuts of the short plate and flank are delicious, but some care must be taken not to render them chewier than what they already are. Let’s discuss exactly what those belly cuts are and then delve into cooking them. The short plate, (or plate for short), is home to short ribs and skirt steaks. Short ribs are yet another exception in that they require a wet-heat cooking method. But for the purposes of the present discussion, I wish to focus on the steaks derived from the plate and flank. Skirt steaks are often the meat of choice for fajitas. They’re also a favorite for topping with the Argentinean condiment chimichurri, a salsa-like sauce made from garlic, hot peppers, herbs, oil and vinegar.

The flank provides hanger and flank steaks. Hanger steak is the classic choice for steak frites, the French version of steak and French fries often found in French brasseries and bistros. Flank steak can certainly be eaten whole, but it’s also popular in Chinese stir-fries whereby it is cut into thin strips. Flank steak can also be employed for fajitas as well. Marinated and sliced flank steak is sometimes referred to as “London broil,” a rather amorphous term that is applied to other cuts such as the round and sirloin.

Skirt, hanger, and flank steaks are relatively thin steaks consisting of long, coarse muscle fibers. They all have very deep, beefy flavors. They can be a little bit chewy and the trick is to prepare and cook them so as to minimize their toughness. There are basically three steps toward that endeavor. First, they all benefit from an overnight marinade. The marinade will tenderize them to a small degree, but even more importantly, will add flavor. The second step is actually the most crucial, namely not overcooking them. If you insist on well done meat then you’d be advised to look elsewhere on the cow, (or the recesses of your mind’s beef conceptions but that’s another story). Skirt, hanger, and flank steaks are at their best done no more than medium-rare. Finally, when slicing them, cut against the grain. As stated, they are all composed of long muscle fibers that are coarse and easily visible. Cutting them with the grain maintains the elongated strands, (and hence a stringy chewiness), while cutting them against the grain shortens them.

These steaks are ideal for grilling and the procedure is very straightforward. Oil your grill and preheat it until it’s very hot. If you’ve marinated the steak, remove the excess marinade and pat dry. Lightly brush them with olive oil and season with at least salt and pepper. Place the steak on the grill and flip it the instant the first side has seared. Sear the second side, (which will take a little less time), and immediately remove and serve. You will see that some of the best eating comes from the belly of the beast. Also Visit Mark’s website: Food for Thought Online

|